In today's fast-paced business environment, organizations constantly seek ways to improve team productivity and foster a culture of continuous learning. One innovative approach to achieving these goals is the Farmers Market activity, created by Erich R. Bühler and published in his book "Leading Exponential Change" in 2018.

The Farmers Market is a dynamic and engaging activity designed to help organizations load balance their teams and optimize their workforce. By allowing employees to self-organize based on their skills, personalities, and job expectations, this practice can lead to the formation of highly motivated and productive teams.

The activity encourages employees to take ownership of their roles and actively contribute to the success of their teams. It also helps to break down silos and promote cross-functional collaboration, as individuals from different departments and backgrounds come together to form cohesive units.

Moreover, the Farmers Market approach can help organizations reduce the "Permission-to-learn" pattern, which often hinders employee growth and development. By fostering a culture of continuous learning and empowering employees to make decisions about their own development, organizations can unlock the full potential of their workforce and drive exponential change.

The following text will explore a real-world example of how one company successfully implemented the Farmers Market activity and the valuable lessons learned from their experience.

A real-world example of the Farm Market

A company where I offered coaching required that two of their software teams learn the Kanban techniques. The training course was approved after two months, and the members were thrilled. It was only at the end of this training that I discovered that the groups surrounding those members were all experts in Kanban. Incredible! Why hadn’t the groups shared this knowledge with each other?

The management team of another company that I helped was initiating an Agile transformation. They had created eight Scrum teams through a tortuous process, mainly because many of the skills were scarce or not available. To overcome this situation, the three managers defined a formal procedure for team members to learn how to act if a new skill was needed. Despite this, the number of rules and exceptions to this procedure remained high, so I proposed an experimental activity called the Farmers Market.

About 100 people would have four hours to create new teams based on their personality and formal and informal skills. I proposed two simple rules:

- Each new Scrum team must have all the skills to successfully implement a product.

- Each team should have a maximum of eight core members.

During subsequent talks, the management team asked two interesting questions:

A. What would happen if one or more people were left out of the teams because others thought they had little knowledge or were not very skilled?

B. What would happen if the employees did not organize themselves and the game failed?

Clearly, this could cause the initiative to lose traction, and it was certainly a risk. But even though those situations could be problematic, I suggested moving forward and finding a solution for such cases if they arose. I even bet a month’s salary that the dynamics would be successful!

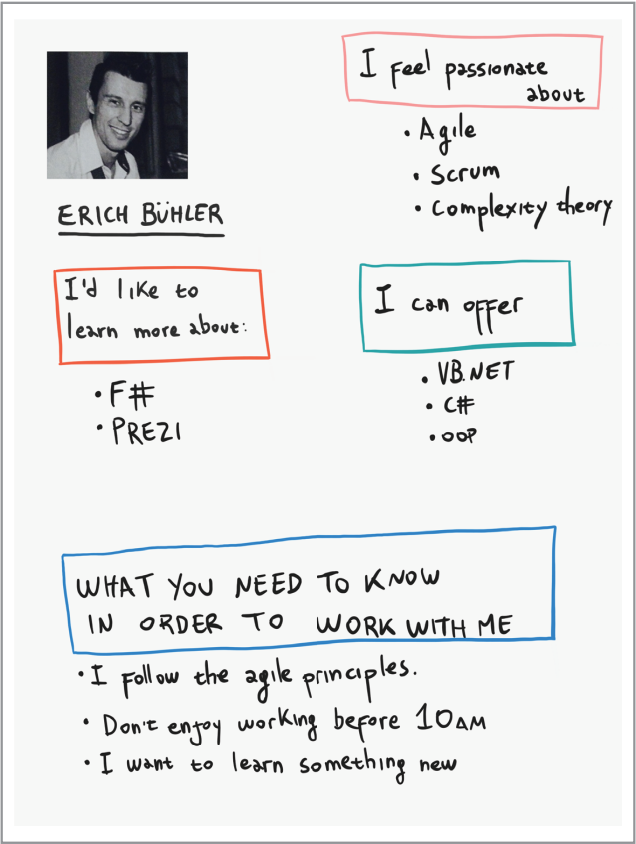

In all honesty, I’m not sure that the bet influenced the management team’s decision, but they finally gave the green light to my Farmers Market proposal. The following day, we asked each of the 100 participants for an informal resume that answered these questions:

- What’s your name?

- Attach a photo for identification.

- What skills do you have?

- What are some recently learned skills that few people know about?

- What do you enjoy doing or have a passion for?

- What should others know to work comfortably with you?

We asked everyone to temporarily forget about the already-existing teams and to give the new dynamic a chance to work. As they were all Scrum teams, there were already eight Product Owners and one Scrum Master per group. The eight Scrum Masters and Product Owners were placed in the center of the room and told that the nearly 100 people would have half an hour to talk with them to learn more about the products to be implemented. It was also an opportunity for them to get to know the Product Owners’ and ScrumMasters’ personalities.

Shortly there after, the energy in the room was high and people were enjoying the dynamics. Everyone wanted to know more about the future t asks and discover each other’s personality. When the time was up, we asked everyone to paste the previously prepared resumes on a wall, and we presented the two rules of the game. We started the timer and gave them four hours to form new teams. People remained motionless during the first two or three minutes.

The managers observed, worried, and asked themselves what was happening. They decided to stand back and give participants the space they needed to find their own solutions. A few minutes later, to the relief of the managers, everyone started speaking, asking questions and moving throughout the room to learn more about the available skills. Soon, individuals began to recruit and form new groups.

Not only did everyone want to know more about their partners’ formal skills, but they also wanted to hear about their recent training and preferences. In addition, they sought out the personal and emotional connections that are key to success.

Without management intervening, the teams began to form, making offers to attract the talent they needed. Forty-five minutes later, something important happened: they discovered that some necessary skills were scarce and that there weren’t enough people with specific knowledge for the number of groups that needed to be created.

Once again, the managers were concerned and considered intervening. I asked that they be patient. A short time later, they were surprised when explicit workingagreements were created between teams, indicating how people would be sharedand how some would act as coaches without being part of the groups. Although we had planned the activity for four hours, it only took an hour and a half for the new Scrum teams to form. After this, we carried out the first work-cycle planning session (Sprint Planning).

Since this activity, the motivation and productivity of these self-organized teams has been surprisingly high. The activity was a success, and I felt confident wouldn’t be losing the month’s salary I had waged. When setting up new teams, the employees didn’t consider only formal and informal skills.

They also valued factors such as personality, learning approaches, and job expectations. This outcome freed management and saved the company thousands of dollars. It also established crucial habits for self-organization and group commitment. Reducing the Permission-to-learn pattern helped create self-managed teams while the company learned exponential forms of work.

Benefits of the Farmer's Market Activity in Companies Exposed to Highly Changing Markets and Accelerated Change

The Farmers Market activity offers numerous benefits to organizations operating in highly dynamic and rapidly changing markets. By fostering a culture of adaptability, continuous learning, and self-organization, this practice can help companies navigate the challenges of accelerated change and emerge as leaders in their respective industries.

- Enhanced Adaptability and Resilience: In today's fast-paced business environment, the ability to adapt quickly to changing market conditions is critical for success. The Farmers Market activity promotes adaptability by encouraging employees to be flexible, open-minded, and proactive in their approach to work. By allowing teams to self-organize based on the skills and expertise needed for each project, the activity ensures that the organization can respond swiftly to new challenges and opportunities.

- Improved Innovation and Problem-Solving: Diverse and inclusive teams are known to be more innovative and better at problem-solving than homogeneous ones. The Farmers Market activity fosters diversity by bringing together employees from different backgrounds, experiences, and skill sets. This diversity of thought and perspective can lead to more creative solutions, breakthrough ideas, and successful innovations.

- Increased Employee Engagement and Motivation: The Farmers Market activity empowers employees to take ownership of their roles and contributions, which can lead to higher levels of engagement and motivation. By allowing individuals to self-select into projects that align with their interests and passions, the activity ensures that employees are intrinsically motivated to perform at their best. This increased engagement can translate into higher productivity, better quality work, and improved overall performance.

- Faster Learning and Skill Development: In highly changing markets, the ability to learn and acquire new skills quickly is essential for staying competitive. The Farmers Market activity promotes continuous learning by encouraging employees to share knowledge, collaborate across departments, and take on new challenges. By exposing individuals to a wide range of projects and experiences, the activity accelerates skill development and helps the organization build a highly capable and adaptable workforce.

- Stronger Collaboration and Teamwork: The Farmers Market activity fosters a culture of collaboration and teamwork by encouraging employees to work together towards common goals. By breaking down silos and promoting cross-functional cooperation, the activity helps to build strong, cohesive teams that can tackle complex challenges and drive innovation. This collaborative spirit can also improve communication, trust, and mutual support among employees.

- Greater Organizational Agility: Agility is a key competitive advantage in highly changing markets. The Farmers Market activity promotes agility by enabling the organization to quickly reconfigure teams and resources based on changing priorities and market demands. By fostering a culture of self-organization and adaptability, the activity helps the company remain nimble and responsive in the face of accelerated change.

- Enhanced Employer Brand and Talent Attraction: Companies prioritizing employee development, collaboration, and innovation are more likely to attract and retain top talent. The Farmers Market activity can help to build a strong employer brand by showcasing the organization's commitment to these values. By creating a culture that values continuous learning, empowerment, and inclusivity, the activity can help attract high-quality candidates looking for opportunities to grow and make an impact.

In conclusion, the Farmer's Market activity offers many benefits to organizations operating in highly changing markets and facing accelerated change. By fostering adaptability, innovation, engagement, learning, collaboration, agility, and a strong employer brand, this practice can help companies build resilient, high-performing teams equipped to thrive in the face of uncertainty and complexity. As such, the Farmers Market activity is a valuable tool for any organization looking to stay ahead of the curve in today's rapidly evolving business landscape.